Written by:

Dr. HO Chi-Ping Patrick

Dr. LUFT Gal

Image source: Internet

The United States’ most powerful military is a hugely expensive instrument of foreign policy essential to ensuring peace, prosperity and order on the entire planet. But in the 21st century, modern wars are almost impossible to win, especially when nuclear powers are involved. But while most societies are becoming less tolerant of the consequences of military confrontation, there are always some who opt for power showdown whenever their direct interests are challenged or at stake. This is why in lieu of military conflict, economic punishments like sanctions and other trade measures have become the go-to solution in U.S. foreign policy.

Sanctions as an instrument of foreign policy are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they are more popular, cheaper and easier to implement than the use of force. All that is needed is an act of the U.S. Congress or presidential executive order or, when international consensus can be reached, a United Nations Security Council resolution. As American President Woodrow Wilson explained a century ago: “It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon that nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.”

Image source: Internet

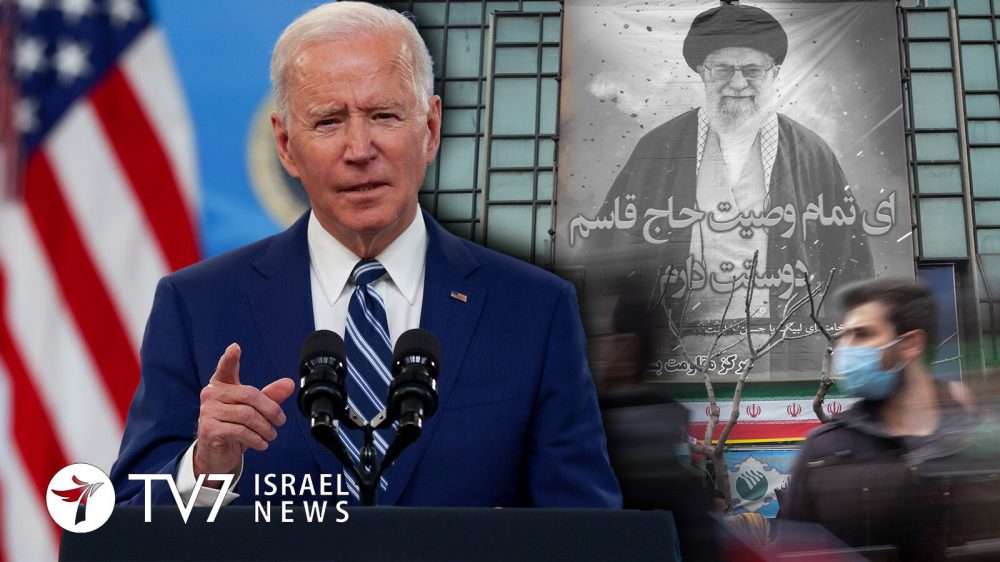

On the other hand, as the economic penalties imposed on countries like Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Cuba, Russia and North Korea have demonstrated, sanctions have not proven to be terribly effective as a way of transforming a country’s behavior. At best they can be used successfully in preparation for tough negotiations, provided they are implemented smartly, in a multilateral fashion and in coordination with other instruments of statecraft.

U.S. economic statecraft has gone through an interesting evolution over the past two decades with regards to the use of sanctions. During the Cold War, U.S. sanctions targeted a country’s entire trade with the rest of the world. So trading Cuban cigars, for example, would be a violation of the sanctions on Cuba. But since September 11, 2001, successive U.S. administrations turned from broad-based trade sanctions to more targeted financial sanctions. In other words, instead of intercepting the flow of goods around the world—cigars in the case of Cuba— the United States started intercepting the flow of money, punishing banks for facilitating payments through the U.S. dollar clearing system.

Image source: Internet

A second innovation in the use of sanctions has been the shift from primary sanctions to secondary ones. Primary sanctions mean that no U.S. person can do business with a sanctioned entity. So, for example, bank X can be sanctioned for doing businesses with an enemy of the U.S., and no U.S. person or entity would be allowed to do business with that bank. Secondary sanctions expand the reach of the sanctions, applying them to non-U.S. entities. This way, an Asian company that wants to do unrelated business with bank X would face the risk of being cut off from the U.S. financial system. Thus, the U.S. essentially tells the world that it has to make a choice: abide by the U.S. unilateral policies and side with the U.S. in stopping to trade with the U.S. enemy, or itself becoming an enemy of the U.S. and suffer what most corporations and businesspeople would consider a financial death sentence.

U.S. law grants the American president almost unlimited powers to sanction foreign states, entities or individuals. These powers go back to 1977 when U.S. Congress passed the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), authorizing the president to block transactions and freeze assets of those who constitute a “threat to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States.” This catch-all mandate is so broad that theoretically at some point or another numerous countries could find themselves on the receiving end of U.S. punitive measures just because their foreign policy is not to America’s liking. Hence, the imposition of economic sanctions has become a kneejerk reaction to almost every transgression on earth as perceived by the American. The International Criminal Court wants to prosecute Americans? Sanctions. North Korea testing a missile? Sanctions. Arrest of an American citizen in Turkey? Sanctions. The temptation to hit the American enemies in their pocketbook is strong and with impunity.

Image source: Internet

Sanctions are not only the president’s option of first resort, they also provide Congress with an opportunity to reassert itself in foreign policy. Activist members of Congress often pick an international issue close to their heart— or the heart of a domestic constituency—and champion it, urging their colleagues to support their pet legislation to sanction this or that. One becomes a champion of Tibet, another of the Copts in Egypt, another of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar, another of the Uygurs in Xinjiang, and yet another of the rioters in Hong Kong. With 535 senators and representatives, some 468 of whom are running for reelection every two years, and with a world that is becoming increasingly complex and fraught with inequalities and disappointment against the hegemon, American adversaries worthy of being sanctioned keep piling up. No wonder President Biden’s administration utilized 34 country-specific sanctions programs in its first year in office: one in six countries in the world is under U.S. sanctions. And then there are countries that are not under any official sanctions program, at least for the moment, but for various reasons are the targets of other economic punitive measures like export controls, tariffs, embargos, etc.—which they view as economic weapons. Objectively speaking, almost every one of the sanctioned countries is targeted for what Washington could not tolerate, be it human rights violations, terrorism, crime, narcotics, nuclear proliferation and other behaviors unbecoming to the American administration. The problem is that the aggregation of so many sanctioned countries, with a cumulative population of nearly 2 billion people and growing, and with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of more than $15 trillion, has created an axis of resentment which has triggered an unprecedented pushback against America’s financial hegemony.

Image source: Internet

U.S. sanctions also target tens of thousands of individuals, companies and state owned enterprises from scores of countries. The individuals and companies are often extremely influential and well-connected in their own countries; their ire with the U.S. has consequences. It is worth taking a look at the list of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) under the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), a division of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. This list contains thousands of names of individuals and entities, and it is growing by leaps and bounds. Since 2001, the number of entities added annually to the SDN list has grown threefold. In 2013, the list was 577 pages long. In 2019, the number of pages was 1,307. Many of those designated are either part of or are closely linked through family or business relations to their countries’ leadership.

Take Russia for example. As part of the response to Russia’s occupation of Crimea, its involvement in the civil war in Syria on the side of Syrian President Assad rather than that of the U.S. and Saudi-supported Sunni insurgents, and its alleged interference in the 2016 elections. A 2017 law called Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which passed the Senate by an overwhelming majority of 98 to 2, required the U.S. Treasury to provide to Congress “identification of the most significant senior foreign political figures and oligarchs in the Russian Federation, as determined by their closeness to the Russian regime and their net worth” as well as an assessment of the relationship between those individuals and “President Vladimir Putin or other members of the Russian ruling elite”. In January 2018, the Treasury submitted a list of 210 prominent Russian political figures and business leaders including 96 “oligarchs” none of whom have been charged with any crime at the time. They just happen to know Putin and probably benefit from their relations with him.

Image source: Internet

In April 2018, the Treasury unleashed sanctions against seven Russian oligarchs with ties to Putin along with 12 companies they own or control and 17 Russian government officials. This means that not only have their assets in the U.S. been blocked but also that U.S. citizens and residents as well as U.S. corporations are prohibited from engaging in any business with them.

But then a major escalation occurred. One of the sanctioned companies was Rosoboronexport, Russia’s main arms export entity, which was placed on the CAATSA blacklist for its support of the Assad regime in Syria. In September 2018, under CAATSA authority, the U.S. imposed secondary sanctions against a Chinese military procurement company called the Equipment Development Department and its director for buying weapons from Rosoboronexport. The director being sanctioned has today become the Chinese Minister with whom the U.S. Secretary of defense was trying desperately to meet in recent days, but failed to meet for good reasons.

Image source: Internet

Through such sanctions, the U.S. extended its jurisdiction to the bilateral trade between Russia and China. These are not just any two countries. These are America’s top two competitors most committed to the de-dollarization effort. While in Washington the move got little attention, in Beijing it sparked a firestorm. It was one of the defining moments which brought China to realize that something must be done to protect its sovereignty and national financial security.

(Inspired by and adopted partly from the book “De-Dollarization” by Dr. Gal LUFT with permission from the author)

Edited by Fang Fang

proofread by Wang Yan